Manchester BRC research shows better understanding of autistic people’s listening difficulties could improve their wellbeing

New research has found that noisy environments can be distracting and pose listening difficulties for autistic people, affecting their social life, emotional wellbeing and career.

One in 67 people in the UK are autistic, which affects the way people communicate and process sensory information such as sight and sound. This can make everyday tasks more difficult.

Previous research lacks autistic people’s personal experiences of listening to speech. In this new study, supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), researchers asked autistic people to describe their experiences in detail.

Nine autistic people were interviewed, aged between 19 and 38 years old, and found that all experienced listening difficulties. The six-person study team included two autistic researchers, to reduce the risk of non-autistic people misinterpreting their experiences.

Common themes emerged during the interviews:

- Participants found noisy environments distracting and distressing. Background sounds drowned out and jumbled voices, and this resulted in difficulties focusing on one target voice. Some participants said they struggled to listen if many conversations were happening at once, preferring one-to-one communication.

- Information from other senses like sight, smell, and pain also caused listening problems. One study participant said they found the scent of strong perfume distracting when trying to listen to a conversation.

- Listening difficulties affected autistic people’s social life, emotional wellbeing and career. One interviewee said they felt ‘terrified’ of going to work in a noisy call centre and another said straining to listen in social situations left them feeling drained.

- A variety of coping strategies were described by participants, which they had generally developed themselves. These included looking at people’s lip movements, moving to a quieter room, wearing high fidelity ear plugs and using subtitles while watching TV.

- Some interviewees hid their difficulties, but this could lead to anxiety and isolation. They also worried that their mishearing or withdrawal from conversations could be mistaken for rudeness.

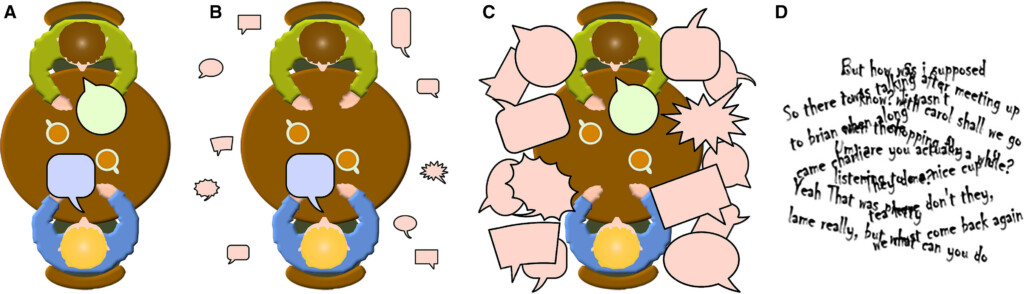

An illustration created by an autistic researcher who worked on this study. It shows the challenges posed to some autistic listeners by common social listening environments, which he dubbed ‘The Café Effect’. The person in blue is autistic, the person in green is neurotypical. (A) The pair attempt conversation in the presence of background noise which is not loud but is composed of multiple voices. (B) When blue speaks, green has some awareness of the background voices, but is not troubled by them. (C) When green speaks, blue experiences significant interference from the background voices. (D) The resulting jumble of sounds makes comprehension challenging.

Participants often felt frustrated by a lack of understanding of their listening difficulties – by friends, family, organisations, and especially by clinicians – which added to the burden.

The research team hope their study will help non-autistic people recognise listening difficulties and make adjustments for them. They also hope it will allow autistic people to recognise their own listening needs and to ask for help.

Hannah Guest is a Research Fellow at Manchester Centre for Audiology and Deafness at the University of Manchester and Hearing Health researcher at NIHR Manchester BRC.

Hannah said: “We asked non-leading questions, but all of the autistic participants in our study reported listening difficulties. We were surprised at how varied they were; the idea that autism involves one kind of listening difficulty is likely mistaken.

“We were also struck by the wide range of impacts on people’s lives. Going against the idea that autistic people are asocial, our interviewees said they wanted to socialise more, but found that listening difficulties made it too hard. A lack of understanding of listening difficulties by people, institutions, and especially clinicians is a huge part of the problem here.

Raising awareness of the issue will hopefully lead to people and organisations making accommodations for autistic people so that they can participate more fully in conversations and everyday life.

This research is part of a wider project called Speech Perception by Autistic Adults in Complex Environments (SPAACE), supported by NIHR Manchester BRC. A larger follow-up study is being carried out to see how common these listening problems are among autistic people.

The study authors are also creating a list of coping mechanisms for dealing with listening difficulties (supplied by autistic people), which they will share with the autistic community.