Artificial intelligence, juvenile arthritis, and the rise of stratified medicine

How could artificial intelligence be used to help tailor treatments for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), a condition which affects 1 in 1,600 children and young people across the UK?

Learn about pioneering research which is kick-starting the movement of stratified medicine for JIA, with insights from Dr Stephanie Shoop-Worrall, MRC Career Development Fellow at The University of Manchester and researcher in the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre’s (BRC) Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases Theme.

Read 13-year-old Trinity’s story as shared by her mum, Rebecca Beesley, who explains why being on the drug methotrexate was a ‘double-edged sword’ for Trinity, who has polyarticular-JIA.

Dr Stephanie Shoop-Worrall

In the early 1980s, treatments for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or ‘JIA’, were bleak: splints on affected limbs, aspirin, steroids, and even gold injections. These were mostly ineffective in controlling the disease, and often left children and young people with long term disability, joint damage, and pain into adulthood.

We now know much more about JIA, which affects around 1 in 1,600 children and young people across the UK.

The first big treatment breakthrough came in the late 1980s with the drug ‘methotrexate’. Previously a cancer drug, given at much lower doses for JIA, meant that suddenly half of children and young people could achieve remission within a year or two.

Nearly two decades later, the second big advance in medication was the introduction of biological therapies. These drugs focus on specific parts of the immune system, and more of these are being released every year.

We’ve gone from too few treatments for JIA, to an ever-expanding catalogue. But which one to try first?

Methotrexate – friend or foe?

While we still don’t know which drug will work best, due to its cost-effectiveness and long ‘tried and tested’ safety record, the NHS pathway dictates that methotrexate is tried first. Given either in tablet or injection form, it works wonders in some children. However:

- Waiting around is not easy

In the time taken to trial methotrexate, reassess, possibly change the dose, wait two to three months to process taking a first biologic, try the biologic, then cycle through the process until something works, JIA is still impacting a young person in almost every aspect of their life.

- Treating right first leads to better outcomes

Young people treated early with more targeted medicines, like early biologics, go into remission faster, and for longer.

- Side effects

Side effects of methotrexate, such as nausea, are alarmingly common – with around half to two thirds of young people experiencing them. This is not the case for the majority of biologic drugs.

While for some, methotrexate is the best option, trialling it in every child and young person is not the optimal approach.

Our MTX story

by Rebecca Beesley, 13-year-old Trinity’s mum

Trinity (left) with her mum, Rebecca (right)

When our daughter Trinity was just two years old, she was diagnosed with polyarticular-JIA, which affects multiple joints.

A diagnosis of JIA can come as a huge shock to many parents who may not be aware that children can get arthritis. In our case, we were aware as I too had the condition since childhood. Yet it still came as a shock.

Trinity was started promptly on methotrexate and we have since had a love/hate relationship with this medication. Initially it didn’t seem to fully control her condition so after six months, the dose was increased and the transformation in her condition seemed miraculous. The pain was all but gone and she was able to walk, run, dance and play again.

To begin with, we found that there didn’t seem to be any significant side-effects. She had no sickness or fear of the injection as she understood that it was helping her.

But after a while, our ‘norm’ became weekends spent leaning over a bin vomiting. The anti-sickness drug she was given seemed to become associated with that feeling of being sick and taking it would ironically induce vomiting.

For someone who had no fear of needles Trinity would become incredibly anxious on ‘injection day’ to the point of running away and hiding under tables screaming that she didn’t want the injection. Our suspicion is that it was never a fear of the injection but how it would make her feel. She didn’t want to endure the nausea and sickness every single week.

Being on methotrexate is a double-edged sword. Her JIA was well controlled for five years on methotrexate. She was considered to be in remission and could stop taking it.

After 18 months, she flared again. Sadly, due to process delays it took six months to get re-started on methotrexate.

Once again it worked! The methotrexate ‘sword’ cut through the pain and got the joint inflammation under control. Trinity was also more receptive to taking anti-sickness medication as we trialled different formats, such as melts/films which dissolved on her tongue and tablets.

With peer support from our Juvenile Arthritis Research charity network, she became ‘braver’ when it came to having the injections. By connecting with others who acted as role-models, she was now able to have injections without a fuss.

But the other side of the ‘double-edged sword’ started to affect her. She experienced the worst fatigue we’ve ever witnessed and needed to be carried upstairs. It was awful and was affecting her constantly.

Despite taking anti-sickness medication, the nausea now seemed to last all week, not just for those first couple of days post-injection. Her education was being dramatically affected as we would often receive phone calls to collect her from school because of how unwell she was feeling.

We know these were side-effects of methotrexate. Things got so bad, she had to stop the methotrexate and then the side-effects stopped too.

It was heartbreaking seeing your child in pain again, needing to use mobility aids including crutches and wheelchair especially when we had hoped that episode in her life was over. I found myself wishing that she was back on the methotrexate as life felt simpler knowing the methotrexate was working and her JIA was well controlled. But Trinity had a different view. She explained “It made me feel sick and depressed and I didn’t have a life.”

Thankfully after several months, the biologic started working effectively. And we were pleased to see that it didn’t have the nasty side-effects that Trinity had experienced with methotrexate. Sometimes, we wish she had been given this option sooner.

Who should try methotrexate?

With so many drugs on the market for JIA, a new term is being banded around at greater volume: stratified medicine. The premise: there are groups (‘strata’) of people that should start on different drugs.

The first step is deciding who should try methotrexate, and who should skip straight to a biologic. Already, those whose arthritis affects their spine go straight onto a biologic. We also have good evidence that a subtype of JIA called systemic JIA or Still’s Disease is best treated immediately with a biologic. But that leaves everyone else whose best drug remains unknown.

A major problem in uncovering treatment groups is the assumption that disease either ‘responds’ or ‘doesn’t respond’ to treatment. In an ideal world, this would be the case – you take the methotrexate and either everything gets better, or nothing gets better. That’s certainly what is assumed in research trials, and is the basis for treatments in clinic. However, in the real world, JIA is far more complex, and drugs might only help to some extent.

Technology of the future

Artificial intelligence (AI) could be used to help the stratified medicine cause.

At The University of Manchester, we have used a type of AI called ‘machine learning’. Using data from the CLUSTER consortium – four nationwide studies totalling nearly 2,000 children and young people with JIA – we got the ‘machine’ to learn patterns of disease across four key areas in the year after taking methotrexate:

- How many swollen, painful joints there were

- How well doctors thought the disease was being controlled

- How well the young people themselves felt

- A blood marker of inflammation called ESR.

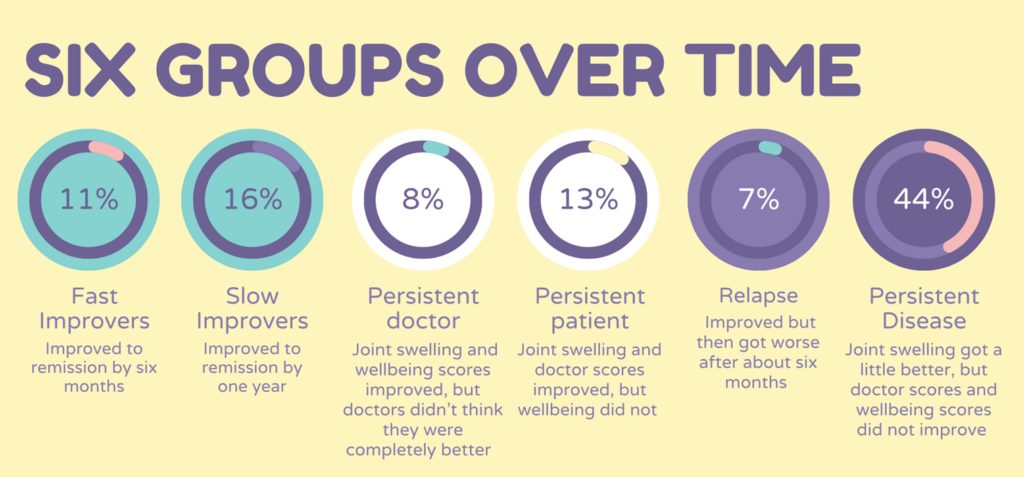

The team found six groups with different patterns over time:

The overall picture was positive: methotrexate will help joint swelling across the board. Beyond this, there were some big differences between the six groups, that affect how we understand methotrexate to work:

- Fast Improvers (11%): JIA improves quickly to remission.

- Slow Improvers (16%): JIA improves more slowly to remission.

These groups are interesting because they reach the same point: remission. But you can only tell if the drug has ‘worked’ if you look at the whole picture, not a single point in time.

- Persistent Doctor (8%): Joint swelling improves, young person feels better, doctors did not think the disease looked completely better

- Persistent Patient (13%): Joint swelling and doctor scores improved, young person did not feel better

This disconnect between how disease looks and how it feels is something young people with JIA have been telling us for a while: sometimes my doctor says I look better, but I don’t feel better. This study shows how common this is, and how seriously it should be taken.

- Relapse (7%): JIA improved but then got worse again

- Persistent Disease (44%): Joint swelling got a little better but doctor scores and wellbeing did not improve

For nearly half of young people, their disease didn’t get much better after taking methotrexate. This was expected, and makes the concept of ‘stratified medicine’ all the more important.

Did their JIA ‘respond’ or ‘not respond’ to methotrexate?

If we normally assume JIA either ‘responds’ or ‘doesn’t respond’ to methotrexate, where does this new evidence now leave us?

The young people that improved quickly after taking the drug easily fit into the ‘respond’ category. And it was easy to put those for whom methotrexate did very little into the ‘doesn’t respond’ category. But what about everyone else?

We have shown that the way we normally tell if drugs work for JIA is inherently flawed. JIA is far more complex, and drugs might only help to some extent.

What next?

This is a first step toward ‘stratified medicine’ for JIA. It has shown groups whose disease responds in different ways after taking the drug, some of whom weren’t truly visible before. It provides a voice to all those young people telling us that they aren’t feeling better, no matter what their disease looks like to their doctors. And it kick-starts the movement to pick drugs and other treatments based on more than trial-and-error.